Lodge History

Muscogee Lodge #116 formed at the beginning of 2023 as a result of a merger of the Indian Waters and Pee Dee Area councils of South Carolina. Since a council may have no more than one OA lodge, Muscogee and Santee merged to create a new lodge, by combining membership and lodge totems, using the “Muscogee” lodge name, and the Santee lodge number, 116.

Service Area

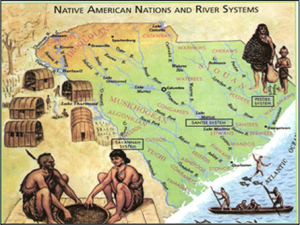

The Indian Waters Council, which stretches over the Midlands and Pee Dee regions of South Carolina. The counties covered are Bamberg, Calhoun, Chesterfield, Clarendon, Darlington, Dillon, Fairfield, Florence, Horry, Kershaw, Lee, Lexington, Marion, Marlboro, Orangeburg, Richland, Saluda, Sumter, and Williamsburg.

Name Etymology & Significance

The Indian Waters Council is named in homage to the South Carolina river systems, which wind paths through the council’s service area, the Midlands and Pee Dee Area Regions of the state, eventually emptying into the Atlantic Ocean. These include the Santee, Pee Dee, Catawba, Wateree, Congaree, Edisto, Saluda, and Salkehatchie rivers[1], all of which take their names from the native tribes that inhabited their banks, prior to the arrival of Europeans. These tribes were neighbors, trading partners, and frequent adversaries of one another as well as with the Cherokee to our northwest[2], Algonquin and Iroquois to the north, and the Muscogee (Creek) to the west[3].[4]

The Muscogee American Indian tribes ranged from the areas in present-day northeastern Alabama, northern and central Georgia, and into western South Carolina, possibly as far as Columbia. The Muscogee was the principal tribe amongst a conglomeration of mixed tribes, who lived on the banks of the many creeks and waterways innervating their tribal areas.[5] When the Europeans came into contact with the Muscogee tribes, they found a significant settlement on Ochese Creek, the present-day Ocmulgee River. Initially called the “Ochese Creek Indians” by the English, the name was gradually shortened to “Creek Indians”.[6]

The Muscogee (Creek) Indians lived in towns, which were occupied by individual families. Those families were divided into clans, some quite powerful, and those clans could be found in most towns. There were some 60 towns by the middle of the 18th century, and each town was ruled by a chief, a vice chief, and a town council. In turn, the Nation was guided by a General Council, which helped decide matters of great significance, such as war and peace.[7]

It should be noted that this confederation of towns and tribes came into being over hundreds (probably thousands) of years, and the attendant civilizations left their marks on the area in many ways. Near present-day Macon, GA, the ruins of once sacred burial mounds may be found, and which are preserved in the Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park.[8] These marvels of ancient engineering can be found in several important sites across the Southeast, including the Santee Indian Mound, located in the Santee National Wildlife Refuge.[9]

In spite of the many antiquities contributed to the Southeastern US and after years of encroachment by European immigrants, the Muscogee Creek Nation was forcibly removed by the US government, following passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830.[10] The Muscogee Creek Nation was relocated to present-day Oklahoma, where the Muscogee (Creek) Nation made their capital in Okmulgee, OK.

1South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, Hydrology Section. An Overview of the Eight Major River Basins of South Carolina, SCDNR, 2013, pp. 2–25.

2Mooney, James. “The Siouan tribes of the East.” Washington Government Printing Office, 1894, pp. 70.

3Swanton, John R. “The Indian Tribes of North America.” Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 145, United States Government Printing Office Washington: 1952, p. 298.

4Savage, Henry. River of the Carolinas: The Santee, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, 1956, p. 16.

5Mooney, James. “Myths of the Cherokee: Extract from the Nineteenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology.” Washington Government Printing Office, 1902, p. 14, p. 382.

6Swanton, John R. “Early history of the Creek Indians and their neighbors.” Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73, United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1922, p. 215.

7“Ancient Creeks.” Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park, National Park Service, www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/upload/Accessible-Ancient-Creeks.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug. 2023.

8“The Mississippian Period.” Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/ocmu/learn/historyculture/upload/Accessible-Mississippian-Period.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug. 2023.

9“Santee National Wildlife Refuge.” FWS.Gov, US Fish & Wildlife Service, www.fws.gov/refuge/santee. Accessed 24 Aug. 2023.

10Groleau, Rick, et al. “Indian Removal.” Africans In America, PBS, 1998, www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2959.html.

11Thornton, Richard L., and Alek Mountain. “A New Understanding of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park.” The Americas Revealed, 6 Feb. 2020, https://apalacheresearch.com/2020/02/06/a-new-understanding-of-ocmulgee-mounds-national-historical-park/. Accessed 17 Dec. 2023.